Audio recording of the article.

There are things common for all cultures, things that make us who we are: fragile and strong; empathetic and desperate; at times giving a hand to those in need, at other times ready to accept help; and our ability to tell stories. Our stories are based on individual memories, emotions, and experiences, and by telling them we shape collective memory, and thus historical and national discourse.

The crucial importance of memories was something that ideological leaders always clearly realized. In different periods and in different countries they tried to distort them, replace them with messages beneficial for their own needs, and silence the truth. Today, among the tools widely used by dictatorial regimes, there is fake news, propaganda, and censorship—all rooted in fear of those in power. And very often not only is freedom of expression at stake, but what underpins it—the freedom of thought.

In my project “The Art of (Not) Forgetting”, which began in February 2021, around 4 months after the start of the protests in Belarus, I tried to use storytelling and photography as a means of opposing the regime of the last European dictator: Alexander Lukashenko. The idea that brought me to address these issues was prompted by the situation I was observing in my country since August 2020. During massive rallies against the rigged presidential election, one of the symbols used by the opposition was the white-red-white flag that refers to the period of an independent Belarus and dates back to 1918. Very soon the regime declared this combination was “extremist” and eventually banned. People wearing clothes, scarves, bracelets, and even socks with the “wrong” colors were detained, fined, and given prison sentences.

On social media, many Belarussians admitted they would often leave their apartments with warm clothes, toilet paper, a toothbrush, and other hygiene products in their backpacks “just in case”. This was in response to reports from people recently released from jails who described conditions as inhumane, unsanitary, and overcrowded. It was also claimed that COVID+ patients were deliberately put in with others to infect them.

In the winter of 2021, the absurdity of the situation reached its peak when a group of 15-year-old teenagers were detained in the city center during the day and elderly women exercising outside were kidnapped from a park on the outskirts of the city. On February 5, 2021, 29-year-old Alexander Nurdinov was given a 3 year sentence in a penal colony for “picking vegetation from flower beds and throwing it at police officers” (his official verdict). Among other absurd sentences Belarussians received in court were as follows: “guilty of showing intention”, “condemning silence”, and “expressing mental solidarity”. And none of these are scenes from a dystopian novel, but the reality for 10 million civilians trapped in a nightmare whose “logic” cannot be explained in terms of critical thinking or human vocabulary.

But the ridiculous verdicts have not ceased since the suppression of the 2020 protests—just a few weeks ago on March 1st, Zhanna Trofimets, an elderly woman, marched by herself to one of the central squares of Minsk and was subsequently arrested and fined 3,040 Belarusian Rubles (around 1,000 USD). Trofimets’ case, as well as the arrests of hundreds of other Belarusians who showed solidarity with Ukraine made it clear: yellow and blue were not welcome in the city streets, either. A student at the Belarusian National Technical University who took a picture of Trofimets’ brave picket was also detained.

All these actions appeared to aim not only at silencing dissent, but also at preventing future generations from knowing and remembering amazing acts of solidarity, the Belarussian’s fight for freedom, and their strong voices in opposing violence and lawlessness.

Apart from its indispensable role in the formation of the history of a nation and civilization, memory also matters at the level of basic survival—it is a guarantee against repeating the same mistakes. Deprived of memories, unable to continue the thread of stories our ancestors have shared with us, we risk returning into the mental and spiritual “middle ages”: halting progress and getting stuck in tragic cycles our grandparents had experienced and warned us against.

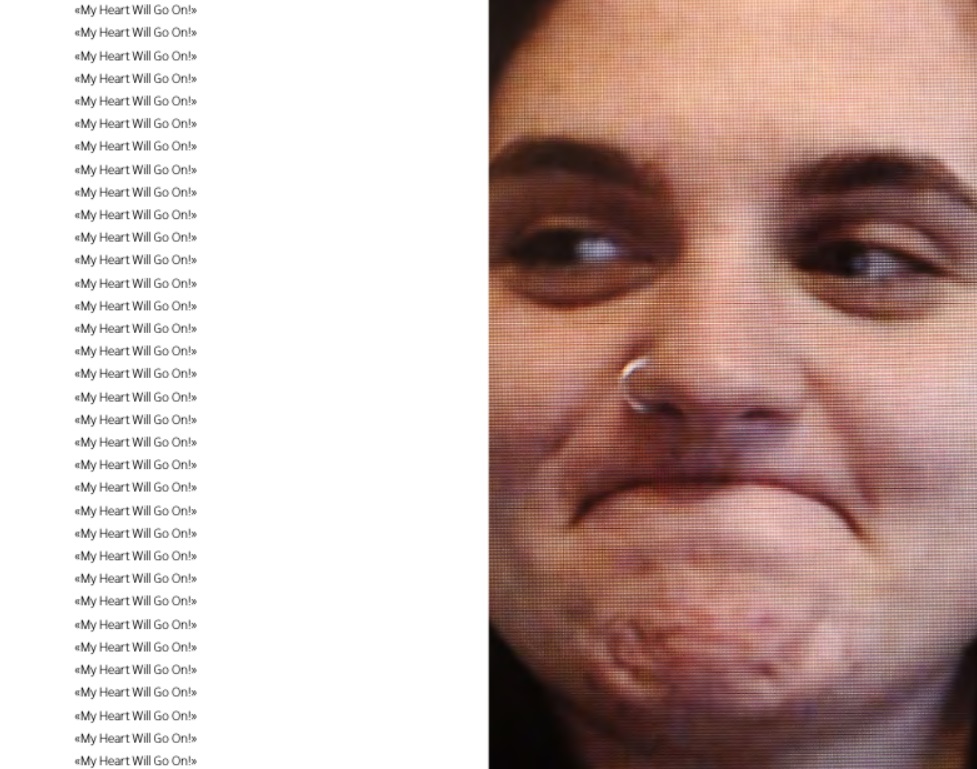

Thus, fueled by this desperate desire to preserve, to keep, to fix down in the form of something more durable that our brain’s “organic memory”, I started talking to the Belarussians about what they would like to remember and what they want to forget. The stories that more than 30 people shared with me were accompanied by images I took of my narrators. Their words were supported by what Umberto Eco has called “mineral memories”: the photos I made were from screenshots (conversations were held via Zoom or Skype) with their particles that I ironically call silicone-generated pixelated palettes.

In “The Art of (Not) Forgetting”, I wanted to address the subject of memory and the process of forgetting and remembering and try to somehow “capture” from the minds of the project’s participants their resourceful recollections, often connected with the events of historical importance.

Flickering with imperfection, fragile and susceptible to transformation, the pixelated images became containers of emotions we experience when retrieving the most resourceful and most painful recollections which ultimately addressed the same basic and ordinary things we all share. These include our feelings when first encountering the death of someone close, the first moment we realized our greater mission, sudden insights via our connection with nature, the world, and ourselves. Our longing for freedom, our helplessness in the face of cruelty and violence. We strive to bring all of this to future generations. We want all of them to be safe from external manipulation and censorship.

Unfortunately, book burning campaigns conducted in 1933 by the Nazi soldiers risk being repeated in Belarus today. Since his first presidential term, Lukashenko has been persistently closing Belarusian-speaking schools and stigmatizing the Belarusian culture as second class and “provincial”, claiming that Russian is “a blessing for all of us”. Since 1994, the Belarusian people have been investing immense effort in the preservation of our national language and culture through underground “partisan” movements. Hopefully, “The Art of (Not) Forgetting” is going to make its own contribution to these processes. By caring for our memories and sharing resourceful episodes with others, we keep our stories alive and feel that we are not alone. There are already too many blank pages in the history of our civilization.

Olga Bubich is a Belarusian freelance journalist, photocritic, and photobooks reviewer, translator, photographer, and lecturer. Her photographs have been shown in group and solo exhibitions in Germany, Sweden, Italy, Holland, Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia. As a freelancer, she has collaborated with a number of Belarusian, Ukrainian, Russian, European, and American media, among which are birdinflight.com, photographer.ru, journalby.com, partisanmag.by, and many others. Since 2000 she has volunteered at the charity organization “Hope for the Future”, accompanying groups of Chernobyl children to Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Canada. She has been a member of the “Month of Photography in Minsk” since 2014.